But people do look at pictures. (- Jeff Patton, again). And sometimes they misinterpret them.

That's why Jeff Patton felt the need to write "Dual Track Development is not Duel Track".

And because people sometimes misinterpret and then misrepresent pictures and ideas and concepts, someone wrote this mischaracterization of not one but at least three first-class concepts: dual-track development, product discovery and refactoring.

This is my attempt to counter the SemanticDiffusion of those concepts by busting some myths and listing some anti-patterns as mentioned in that article.

What not to think, aka myths

Myth 1: Dual-track scrum is an organizational structure separating the effort to deliver working software from the effort to understand user needs and discover the best solution.

It's not an organizational structure.

It's a way of working - a pattern which lots of people doing rigorous design and validation work in Agile development have arrived at. It may be an (intra-team) work organization mechanism, but organizational structure is just the wrong way to do it, because...

It's not about separating the effort to deliver from the effort to understand.

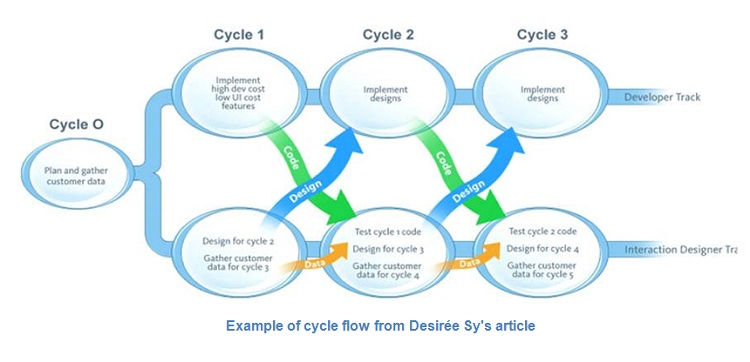

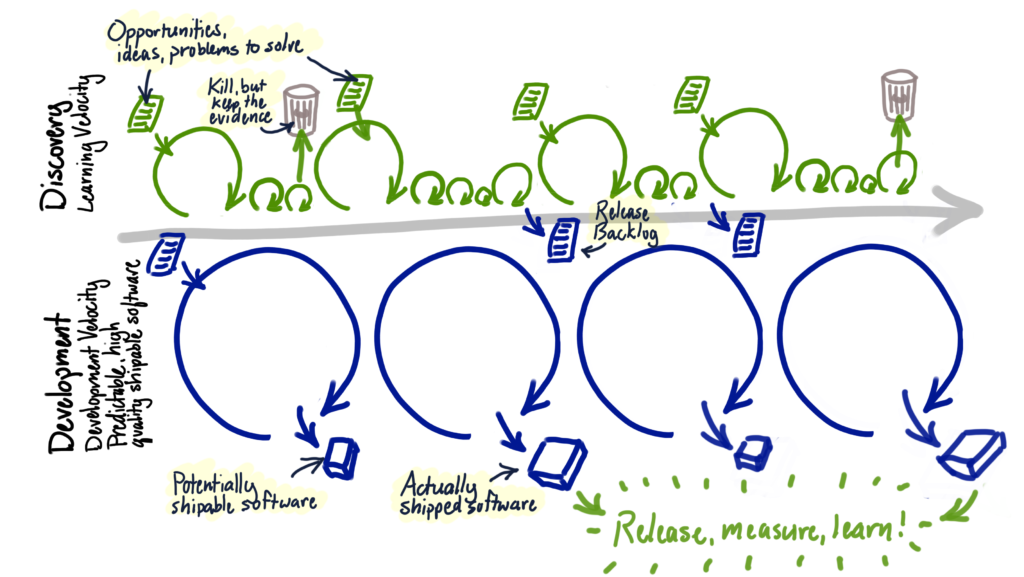

Jeff Patton has used two different visualizations to represent the dual-track model.

|

| Intertwined model |

|

| Conjoined model |

Neither is perfect, but each one is really trying to convey how Agile thinking and product thinking work together in the same process.

The original paper about dual-track development (when it wasn't called that) says:

"... we work with developers very closely through design and development. Although the dual tracks depicted seem separate, in reality, designers need to communicate every day with developers."Discovery work happens concurrently and continuously with development work.

It's not (really) about discovering the best solution.

It's primarily about discovering:

- enough about the problems we’re solving to make good decisions about what we should build

- if we're building the right thing (not the best solution) and if we'll get value in return

- if people have the problem we’re solving and will happily try, use, and adopt our solution

- risks and risky assumptions in our ideas and solution options

Myth 2: Discovery is no more than purposeful iteration on solution options.

Discovery is a whole lot more about validation of problems to solve, opportunities and ideas than it is about iteration on solution options.

Myth 3: Knowledge comes from having thought things through beforehand. The discovery process is where that detailed analysis takes place.

The ability to think things through comes from knowledge, not the other way round. Without knowledge, thinking things through will only generate ideas, options and assumptions (which is all great, too - and you may feed those into discovery).

But no, discovery isn't where detailed analysis takes place - it's where exploration and validation takes place. Yes, to actually start building software, you’ll still need to make a lot of tactical design decisions. It’s often that designers need to spend time refining and finishing design work in preparation for writing code. That's why Jeff Patton clarifies, "OK, it’s really 3 kinds of work".

Myth 4: Refactoring is natural when you’re pivoting.

Refactoring is the process of changing a software system in such a way that it does not alter the external behavior of the code yet improves its internal structure. Pivoting, on the other hand, is a structured course correction designed to test a new fundamental hypothesis.

So, one requires preserving external behavior while the other is hard to imagine without changing external behavior. So, what's natural when you're pivoting is some form of rework - maybe a redesign, maybe a rewrite - but refactoring doesn't seem to be it.

Myth 5: If you're experiencing frequent refactoring, you probably aren’t putting enough effort into product discovery. Too much refactoring? You may need to invest in product discovery.

Contrarily, if you're experiencing infrequent refactoring, you probably aren't putting enough effort into product upkeep and evolution. Too much rework? You may need to invest in evolutionary engineering skills.

Myth 6: Those weeks of refactoring are a direct drag on speed.

Development work focuses on predictability and quality. Discovery work focuses on fast learning and validation.

Refactoring is what enables you to maximize learning velocity in discovery and delivery velocity and predicability in, well, delivery. The knowledge that you can come back and safely and systematically improve quality (read refactor) allows you to avoid wasting time over-investing in quality stuff when you're uncertain about the solution. Reflecting your learning in the code and keeping its theory consistent and structure healthy through MercilessRefactoring brings predictability and speed to development because you aren't constantly thrown off by surprises lurking in the code.

On the other hand, if you're spending weeks refactoring, you're likely not refactoring (but doing some other form of rework) or, ironically, not refactoring enough.

Myth 7: And “we didn’t think of that” is still a flaw even if you weren’t “supposed to.”

If your weren't supposed to think of something, and so you didn't, it's not a flaw - it's just called not being psychic.

What not to do, aka anti-patterns

Anti-pattern 1: Each track is given a general mandate: discover new needs, or deliver working software. Taking the baton first, the Discovery track is responsible for validating hypotheses about solving user problems, and preparing user stories for the Delivery track.

This sounds suspiciously like talk of two teams rather than two tracks within a single team and a single process. If the whole team is responsible for product success, not just getting things built, then the whole team understands and contributes to both kinds of work.

Anti-pattern 2: A sampling of "how it plays out in my current environment":

- The initial solution concepts are built from the needs brought to the team by Product Management. These often come from known functionality needs, but sometimes directly from client conversations.

- Product Manager provides a prioritized list of user needs & feature requests and helps to explain the need for each.

- The Discovery track generates an understanding of requirements, wireframes and architectural approach.

- The Delivery track takes the artifacts generated in the Discovery track and creates the detailed user stories required to deliver on those ideas.

- The handoff between Discovery and Delivery turned out to be a little hairy.

First, if you already have a prioritized list of requirements/known needs (that only sometimes come directly from client conversations) and can already explain the need for each, where's the element of discovery? You either don't need it, or aren't doing it (right).

Secondly, instead of building a shared understanding of user needs and potential solutions by working together as a whole team, if one group of people in generating an understanding of requirements and handing off artifacts to another group of people, don't be surprised if the handoff turns out to be a little hairy.

Anti-pattern 3: [A variety of specialists] whiteboard wireframes and talk through happy path and edge cases to see if a design holds water. When it doesn’t, changes are made and the talk-through happens again. Simple features may require only a few iterations; more complex ones may be iterated on for several weeks off and on, woven in with other responsibilities. When the team is confident in the design, [...] members of client facing teams are invited to a walk-through, and select clients are recruited to provide feedback.

The team iterating until it feels 'a design holds water' isn't learning and isn't validation and isn't discovery. Sure, it's progressive refinement of ideas and solutions through deliberate analysis and thinking through. And those are wonderful things and should done. However, that's not discovery, so don't call it that.

What to do instead

I've tried to clarify what dual-track development is not, without properly explaining what it is. Others have done a much better job of it than I could at this point, so here're some starting points:

- Adapting Usability Investigations for Agile User-centered Design

- Dual Track Development is not Duel Track

- Dual-Track Agile

- Model-Minded Development

- WardExplainsDebtMetaphor, but also, what he really explains is some of the essence of lean startup and lean product development

No comments:

Post a Comment